- Home

- Stephen Brunt

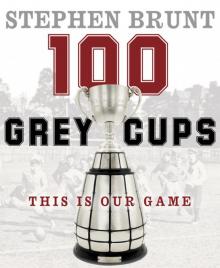

100 Grey Cups Page 14

100 Grey Cups Read online

Page 14

The infamous Mud Bowl of 1950.

The final score was 37–20. Baltimore quarterback Tracy Ham was named the game’s most valuable player, but in truth the win was in every way that mattered a total team victory by one of the best in CFL history. Counting the regular season and playoffs, the Grey Cup victory was the Stallions’ eighteenth of the season. No CFL team had done that before, and none has since.

Tracy Ham moved from Toronto to Baltimore with the U.S. expansion. Both years there he made it to the Grey Cup final, winning the second year.

In the dressing room after the game, the Stampeders players couldn’t help but feel that they had disappointed more than just their hometown fans. In each of the previous two seasons, they had entered the playoffs as Grey Cup favourites, and both times, they had floundered before even reaching the big game.

But this loss felt worse.

“We let the country down,” linebacker Matt Finlay said. “It’s a sad day for Canada. I’ve loved the CFL my whole life. Everyone wanted to keep the Cup in Canada.”

Only receiver Dave Sapunjis tried to take the long view.

“It’s sad for us,” he said. “But maybe this will be good for CFL football in the United States. Maybe this will spark a little more interest in our game down there.”

As he prepared to transport the Grey Cup outside of Canada for the first time, the champions’ owner, Jim Speros, seemed wildly confident about the future. He knew that the Browns – renamed the Ravens – were coming to Baltimore for the 1996 season, which probably meant that the Stallions, who been drawing close to 30,000 fans a game at the old Memorial Stadium, would have to pack up and move elsewhere.

But they’d find a new home, he assured everyone. He was talking to all kinds of different people. The NFL’s Houston Oilers were leaving for Tennessee. Maybe Houston was where the CFL would land next.

“It’s back to business for us,” Speros said. “But I’ve got a heckuva lot more leverage whatever I do. I’m carrying a proud chip on my shoulder tonight.”

Who could have imagined in that moment that, by the time the next season began, the Grey Cup champions would not only be all that remained of the American expansion? Just as had been the case in Baltimore, they would find themselves in a city a beloved football team with a glorious past had fled years before.

Where the death of the American experiment led, indirectly, to the return of the CFL to Montreal – not by grand plan, not by design, but because there was no alternative.

In 1996, the Baltimore Stallions became the new Montreal Alouettes, and there, their story would play out like a fairy tale.

2001

THE MONTREAL RENAISSANCE

The Alouettes after winning the 2010 Grey Cup in Edmonton.

Never mind in the Canadian Football League – in any sport, in any era, this is one of the best, least likely, most poetic pulled-straight-from-a-movie-that-you-wouldn’t-believe-for-a-second storylines – and one complete with a happy ending. How football was reborn in its birthplace, Montreal, is a tale that never gets old with the telling.

In 1987, after a long and painful decline, the Montreal Alouettes folded. It happened fast, on the brink of a new season. Suddenly, a franchise established in 1946, the team of Sam Etcheverry and Hal Patterson, of Sonny Wade and Don Sweet and Johnny Rodgers, with roots stretching back to the nineteenth century, was consigned to history, and too few tears were shed. Montreal had lost interest. The Olympic Stadium, once packed with more than 50,000 fans a game, was all but empty. Big-name player signings made no difference. A long love affair had simply burned out.

Nine years later, the CFL found itself in the midst of an identity crisis. Its attempt to expand to the United States had crumbled all at once. Only the most successful of the American teams, the Grey Cup champion Baltimore Stallions, had any interest in staying in business, and because the NFL was about to push them aside at venerable Memorial Stadium, the Stallions had become a team in search of a home. Other cities – other American cities – were floated as possible destinations, before it became clear that the U.S. was no longer a viable option for the league. That left only one place in Canada with a suitable stadium: Montreal. The Stallions were rechristened the Alouettes and set up shop at the Big O, and in the beginning, it seemed that almost no one cared. The tiny crowds that turned up looked lost in the huge stadium. Few betting people would have laid a nickel on the new Als’ chances for long-term survival.

But unbeknownst to just about everyone outside of the province of Quebec, something was happening there. Even in professional football’s absence, the game at the grassroots level had been experiencing tremendous growth. In the CEGEPs, in the universities, young Quebeckers were playing and loving the sport that took hold when McGill University met Harvard way back in 1874.

So football was alive and well. All that was required to turn Quebeckers into fans again was a catalyst, something to make the old seem new – and the old seem new.

It is no small irony that the forced move of the Alouettes to another, much smaller, much funkier home, a place literally falling down around them, created the necessary spark. Forced out of Olympic Stadium for a playoff game by a previously scheduled U2 concert, the Als had nowhere to go but a crumbling old park on the downtown campus of McGill. It was no one’s bright idea. It was the product of no genius marketing strategy. It was in every way a desperation move. And at kickoff time between the Alouettes and the B.C. Lions, it seemed as though nothing had changed in terms of the city’s indifference: the stands looked pretty much empty.

But then, as the traffic congestion that had been holding them back began to ease, the fans started to arrive, to fill the place. A crowd that was young and fun-loving and drawn by the novelty of a game played right in the heart of a great, vibrant city, in cozy, atmospheric confines, by a team they were suddenly ready to embrace. The party that began that day continues unabated.

Of course, it didn’t hurt that the team Montreal inherited from Baltimore was a powerhouse, a winner right off the bat.

On November 24, 2002, the circle was completed, when the new Alouettes arrived at Commonwealth Stadium and won the first Grey Cup for the city since 1977, defeating their historic nemeses, the hometown Eskimos, 25–16.

A heck of a lot had happened in the interim – there’d been ups and downs, death and resurrection – but by the time the trophy was raised, there was no argument that a new golden era of Montreal football was underway.

The long shared history of the sport of football and the city of Montreal divides neatly into five distinct chapters, one of which is the dark period when there was no team at all.

It begins, of course, at the very beginning, with the founding of the Montreal Football Club in 1868, and with the match between McGill University and Harvard University in 1874, which is generally regarded as the birth of the North American game. What the teams played that day would look a whole lot like rugby to a contemporary fan, and afterwards the Canadian and American games went their separate ways, occasionally cross-pollinating but evolving with several key distinctions in their rules, most notably the number of downs, the number of players, and the size of the field (the latter codified in the U.S. because they needed to fit the game into already-constructed stadiums that couldn’t accommodate anything larger).

In 1907, the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union – the precursor of the CFL’s Eastern Division – was formed, a body that would forevermore be known as the Big Four, with Montreal a charter member along with Toronto, Hamilton, and Ottawa.

Montreal’s only pre-Alouette Grey Cup victory came in 1931, when the team was named the Winged Wheelers. (Finding the right moniker for the local club was an ongoing process: they were also at times known as the Hornets, the Indians, the Cubs, the Royales, and, much later, the Concordes.) The opponents that year were the Regina Roughriders, who came east with the usual high hopes. They thought they had seized an advantage when, the night before the game at Molson Stadium, they

hired a local cobbler to add cleats to their boots, at a cost of $67. But the big day dawned, the weather was wintry and the field (a recurring Grey Cup theme) was frozen solid. Wearing cleats, the Regina players might as well have been wearing skates, while the home team got lots of grip by wearing running shoes. The game is remembered for the first touchdown pass in Grey Cup history, a 24-yard strike from Montreal’s quarterback Kenny Grant in the third quarter. Beyond that, the home team was in control from start to finish, winning 22–0. The only thing marring the victory celebration was an unfortunate incident immediately after the game, when Montreal’s Red Tellier levelled Regina’s George Gilhooley with a punch. Tellier was banned for life by the Canadian Rugby Union – the only suspension in Grey Cup history – though three years later, in a forgiving mood, the organization reinstated him.

Montreal football fell into decline thereafter. In 1936, the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association abandoned the sport, and teams that came after sputtered and nearly died. Following the Second World War, as football across Canada was returning to normal and the foundation of what would become the CFL was being put in place, three investors – Lew Hayman, Léo Dandurand, and Eric Cradock – bought the Montreal Big Four franchise, and after some consultation with the public, rechristened the team the Alouettes after the traditional song – a savvy and appropriate acknowledgement of the French-speaking majority in Quebec.

The Als were a hit right from the start. With the masterful Hayman in charge of building and coaching the team, they finished their inaugural season tied with the Toronto Argonauts for first place, and fans packed Delorimier Stadium – even though the home of the Montreal Royals baseball team wasn’t exactly perfect for football, with the pitcher’s mound right in the middle of the field. They lost to the Argos in the Big Four playoff (Toronto would go on to win the 1946 Grey Cup). Three years later, the Als finished second in the east, beat Ottawa in a two-game playoff, knocked off the Hamilton Tigers (back-to-back champions during a two-year stint in the ORFU) 40–0, and advanced to the Grey Cup game in Toronto against the defending champion Calgary Stampeders.

Once more, the conditions of the field were a problem – at least for the Stamps, who were outraged that no one had covered it with a tarpaulin during the snowy week before the big game. “We’ve just witnessed some bare-faced larceny,” Stamps president Tom Brooks said afterwards, a reaction some might have construed as sour grapes. “Fans don’t want to see a bunch of guys sliding around on their bellies or their backsides in a national final. The fans were robbed.” The slippery pitch didn’t seem to faze quarterback Frank Filchock, lineman Herb Trawick, or any of the other Alouettes stalwarts, as they comfortably won the new team’s first Grey Cup, 28–15.

The 1874 McGill–Harvard football game pictured here is regarded as the birth of North American football.

It would be twenty-one long years before Montreal’s next championship, which suggests that there was a long, bleak era in the city’s football history. But in fact it was during that drought that the sport enjoyed its first golden age in Montreal, with Sam “the Rifle” Etcheverry, a strong-armed quarterback from the University of Denver, and “Prince” Hal Patterson, a wonderfully gifted and elegant receiver from Kansas, who could play nearly every position on both sides of the ball, rivalling Maurice Richard of the Montreal Canadiens as the city’s biggest sporting stars.

Sam Etcheverry set a record for most passing yards in a Grey Cup game (508) in the 1955 Grey Cup game, a loss to the Edmonton Eskimos. His record stands to this day.

Three years in a row, the Alouettes went to the Grey Cup, in 1954, 1955, and 1956, and three years in a row they lost to the Edmonton Eskimos, by ever-increasing margins. The first one hurt the worst. Up by five late in the game and driving for another score, Chuck Hunsinger fumbled after taking a hand-off from Etcheverry, and Jackie Parker scooped up the ball and ran it back 90 yards for the deciding touchdown. Montreal fans and players would argue endlessly that it wasn’t a fumble at all, but rather an incomplete illegal forward pass directed at lineman Ray Cicia, which should have resulted in a penalty, but not a turnover. Referee Hap Shouldice disagreed, and the Eskimos triumphed 26–25. Edmonton won again, 34–19, in the 1955 championship game, despite the fact that Etcheverry threw for over 500 yards, and then crushed the Als 50–27 in the 1956 Grey Cup.

ON THE DAY

IN 2001, A YEAR in which the CFL was dominated by its eastern teams, the western representative in the 89th Grey Cup had a losing regular-season record for the first time in league history. Edmonton captured first place in the West Division with an abnormally weak 9–9 record, while Calgary and B.C. earned playoff spots with marks of just 8–10. The East Division champion Winnipeg Blue Bombers finished up at 14–4 and made it past Hamilton easily to reach their twenty-second Canadian football championship game. Their lineup featured three Most Outstanding Player award-winners, led by quarterback Khari Jones, top Canadian Doug Brown, and offensive lineman Dave Mudge, plus Charles Roberts in his rookie season. On paper this game looked to be a blowout, but as it turned out on the day, the regular season often doesn’t count for much.

The game’s final stats package suggests an even match. Turnovers were equal; first downs, net yards, and sacks almost the same; passing little different; and each team had a 100-yard receiver – Marc Boerigter for Calgary and Milt Stegall for Winnipeg. If there was a statistical advantage at all, it was Calgary’s ability to hang on to the ball – they had the ball for 33:02 and made a few more second-down conversions.

The 2001 contest was decided by yet another unlikely hero on special teams, long considered a vital part of the CFL game. Heading into the game, Winnipeg boasted the league’s top punt returner in Charles Roberts, while Calgary countered with the league’s top kickoff-return specialist and overall yardage leader in Antonio Warren. The two kickers, Mark McLoughlin of Calgary and Troy Westwood of the Blue Bombers, had had off years and weren’t much better in the Grey Cup, making only 3-of-7 on the day. So the game came down to a Grey Cup rarity: a blocked punt.

With Winnipeg stopped at their own 35-yard line late in the third quarter, the hero for Calgary became Willie Fells, who ran in a punt blocked by Aldi Henry from the 11-yard line to turn the game around and provide Calgary with a 24–12 lead. The Stamps withstood a late rally, and after McLoughlin’s successful field goal, with 48 seconds left, Calgary had its fifth Grey Cup title in hand. The closeness of the statistics, and of the game itself, underlines the essential parity to be found in a league that has had, for the most part, only eight or nine teams since 1945. What it also shows is that “on the day,” past performance may not mean much, and that Grey Cups are won in a variety of ways.

Etcheverry and Patterson played on, but the Als no longer ruled the east. In 1960, Alouettes owner Ted Workman and general manger Perry Moss decided it was time for a change, seeing signs that Etcheverry was reaching the end of the road. They engineered what is remembered in Montreal as one of the worst trades in sports history, sending Etcheverry and Patterson to the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in return for the Ticats’ own star quarterback, Bernie Faloney, and defensive lineman Don Paquette.

Montreal fans reacted angrily, seeing the two greats shipped out of town. They became even angrier when they learned that Etcheverry had a no-trade clause in his contract, one that management clearly violated. Etcheverry then declared himself a free agent and signed with the St. Louis Cardinals of the National Football League. So Faloney stayed in Hamilton, where the Ticats dominated the east through much of the following decade. With his new team, Patterson would be catching passes from Faloney, and from succeeding Ticat quarterbacks, until an injury forced Patterson into retirement in 1967. And Don Paquette, a very good player but no superstar, became the answer to a trivia question.

The Alouettes all but disappeared from the radar in the 1960s. It was a desperate period, with only the genius of running back George Dixon providing any relief from nine consecutive losing seasons.

&nbs

p; GREY CUP RIVALRIES

OF THE NINETY-ONE GAMES played since Edmonton was the first western team to go east and contest the Cup, twenty have matched the Eskimos against Montreal or pitted Winnipeg against Hamilton. The latter rivalry was played out mainly from 1953 to 1965, but the former – Edmonton and Montreal contests – seem to crop up repeatedly across Canadian football history. No other head-to-head matchups come close to these two great rivalries with the exception, perhaps, of the six Argonaut–Winnipeg games up to 1945.

Edmonton and Montreal’s three consecutive meetings between 1954 and 1956 produced some of the greatest games and individual feats in Grey Cup history: Jackie Parker’s 90-yard game-winning fumble return; Red O’Quinn’s record 290 receiving yards; and the three highest total offensive outputs of all time. The Canadian Football Hall of Fame has inducted a whopping fourteen players from these two teams. The clubs met again five times in a six-year span in the 1970s, with Montreal finally winning in 1974 and 1977. All told, of Edmonton’s twenty-four Grey Cup appearances, eleven have been against Montreal. The Als have played other clubs just seven times.

Winnipeg and Hamilton grabbed the stage in 1957 and dominated the game for almost a decade. They first met in 1935 and 1953, and would lock horns six more times by 1965. The Blue Bombers won four of the teams’ six meetings between 1957 and ’65, including the first Grey Cup to go into overtime, in 1961, and the Fog Bowl, played over two days in 1962. In the latter game alone, there were fourteen eventual Hall of Famers in the two lineups, along with many builders of the game among the two clubs’ management groups.

100 Grey Cups

100 Grey Cups